Chapter 7 Improvement Strategy (Slack & Lewis)

A large body of work has grown around how processes can be developed, enhanced and generally improved.

Processes improvement strategy explicitly declares the organisation's aspiration to develop and improve processes on a more routine basis with important objectives, goals and methods specified as strategy.

Importance of Improvement

Process Improvement gives competitive advantage.

‘The companies that are able to turn their . . . organisations into sources of competitive advantage are those that can harness various improvement programs . . . in the service of a broader [operations] strategy that emphasises the selection and growth of unique operating [capabilities].’

Process improvement

Two strategies are now recognized: breakthrough improvement and continuous improvement.

Breakthrough improvement

Breakthrough, or ‘innovation’-based, improvement assumes that the main vehicle of improvement is major and dramatic change in the way the operation works – the total redesign of a machining from general purpose machine tools to flexible manufacturing system.

The impact of these improvements is relatively sudden, abrupt, and represents a step change in practice (and hopefully performance). Such improvements are rarely inexpensive, usually calling for high investment, and frequently involving changes in the product/service or process technology.

A frequent criticism of the breakthrough approach to improvement is that such major improvements are, in practice, difficult to realise quickly.

Continuous improvement

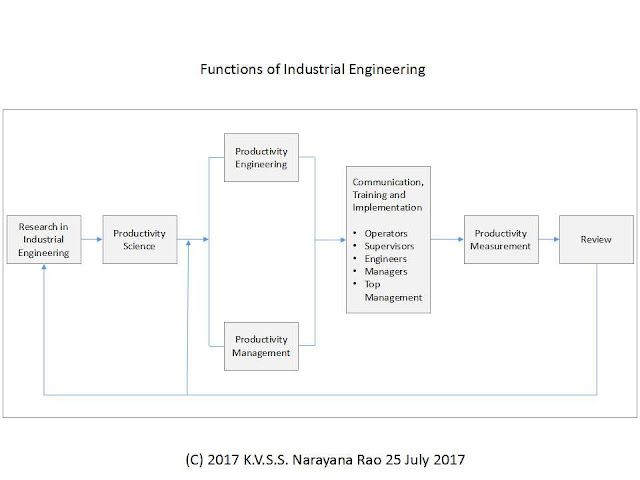

Continuous improvement, as the name implies, adopts an approach to improving performance that assumes more and smaller incremental improvement steps. Industrial engineering studies are concerned with continuous improvement. This has now became more popular as kaizen under the mania for using Japanese terminology.

Continuous improvement does see small improvements as having one significant advantage over large ones – they can be followed relatively painlessly by other small improvements. Continuous improvement becomes embedded as the ‘natural’ way of working within the operation.

Some emphasize that, in continuous improvement (exclusively bottom up improvement) it is not the rate of improvement that is important; it is the momentum of improvement. It does not matter if successive improvements are small; what does matter is that every month (or week, or quarter, or whatever period is appropriate) some kind of improvement has actually taken place.

Both breakthrough improvements and continuous improvement are to be implemented by organizations. Break through improvements are spearheaded by product and process engineering departments. Continuous improvement related to productivity is directed and managed by industrial engineering department. Quality improvement is managed by quality department. Delivery reliability is the responsibility of production planning department. Improvement teams interact and collaborate.

Improvement strategy in Manufacturing Strategy. Three ways are to be planned. Improvements by Process Engineers - Improvements by Industrial Engineers - Improvements by Operators and their Supervisors and Managers. - Narayana Rao (4 Feb 2021. Shared on Social Media)

Improvement cycles

Continuous improvement occurs in cycles repeatedly – a literally never-ending cycle of repeatedly questioning and adjusting the detailed workings of processes.

Degree of process change

Modification - Extension - Development - Pioneer

Direct, develop and deploy

The strategic improvement cycle we describe employs the three elements of direct, develop and deploy, plus a market strategy element.

Direct.

Some authorities argue that the most important feature of any improvement path is that of selecting a direction (Total Productivity Management). A company’s intended market position has to provide direction to how the operations function builds up its resources and processes.

Even micro-level, employee-driven improvement efforts must reflect the intended strategic direction of the firm.

Develop.

Within the operations function those resources and processes that are expected to contribute to competitive advantage are increasingly understood and developed over time so as to establish the capabilities of the operation. Essentially this is a process of learning.

Deploy.

Operations capabilities need to be leveraged into the company’s markets. These capabilities, in effect, define the range of potential market positions which the company may wish to adopt. But this will depend on how effectively operations capabilities are articulated and promoted within the organisation.

Market strategy. The potential market positions that are made possible by an operation’s capabilities are not always adopted. An important element in any company’s market strategy is to decide which of many alternative market positions it wishes to adopt. Strictly, this lies outside the concerns of operations strategy.

Process of Setting the Direction

Performance Planning Monitoring, and Control

Performance measurement

Performance measurement based on performance plans gives the inputs for planning improvements.

Performance measurement, concerns four generic issues:

● What factors should be included as performance targets?

● Which are the most important?

● How should they be measured?

● On what basis should actual against target performance be compared?

Which are the most important performance targets?

So, for example, an international company that responds to oil exploration companies’ problems during drilling by offering technical expertise and advice might interpret the five operations performance objectives as follows:

●● Quality. Operations quality is usually measured in terms of the environmental impact during the period when advice is being given (oil spillage, etc.) and the long-term stability of any solution implemented.

●● Speed. The speed of response is measured from the time the oil exploration company decides that it needs help to the time when the drilling starts safely again.

●● Dependability. Largely a matter of keeping promises on delivering after-the-event checks and reports.

●● Flexibility. A matter of being able to resource (sometimes several) jobs around the world simultaneously, i.e. volume flexibility.

●● Cost. The total cost of keeping and using the resources (specialist labour and specialist equipment) to perform the emergency consultations.

Some typical partial measures of performance

Quality

Number of defectives of the process per unit time

Level of customer complaints

Scrap level

Warranty claims

Mean time between failures of the product

Customer satisfaction score

Speed

Order lead time

Actual versus theoretical throughput time

Cycle time

Dependability

Percentage of orders delivered late

Average lateness of orders

Proportion of products in stock

Schedule adherence

Flexibility

Time needed to develop new products/services

Range of products/services

Machine change-over time

Average batch size

Time to change schedules

Cost

Productivity of resources

Utilisation of resources

Labour productivity

Added value

Efficiency

Cost per operation/process hour

Benchmarking

Another very popular, method to drive organisational improvement is to establish operational benchmarks. By highlighting how key operational elements ‘shape up’ against ‘best in class’ competitors, key areas for focused improvement can be identified.

Types of benchmarking

There are many different types of benchmarking some of which are listed below.

● Competitive benchmarking is a comparison directly between competitors in the same, or similar, markets.

● Non-competitive benchmarking is benchmarking against external organisations that do not compete directly in the same markets.

● Performance benchmarking is a comparison between the levels of achieved performance in different operations.

● Practice benchmarking is a comparison between an organisation’s operations practices, or way of doing things, and those adopted by another operation.

Importance–Performance Mapping

From market requirements the following are established:

● the needs and importance preferences of customers; and

● the performance and activities of competitors.

Both importance and performance have to be brought together before any judgement can be made as to the relative priorities for improvement. Both importance and performance need to be viewed together to judge improvement priority.

The importance–performance matrix

The priority for improvement that each competitive factor should be given can be assessed from a comparison of their importance and performance. This can be shown on an importance–performance matrix which, as its name implies, positions each competitive factor according to its score or ratings on these criteria.

The sandcone theory

Some writers believe that there is also a generic ‘best’ sequence in which operations performance should be improved. The best-known theory of this type is sometimes called the sandcone theory. The theory originally proposed by Kasra Ferdows and Arnoud de Meyer is as follows.

The sandcone model incorporates two ideas.

The first is that there is a best sequence in which to improve operations performance; the second is that effort expended in improving each aspect of performance must be cumulative. In other words, moving on to the second priority for improvement does not mean dropping the first, and so on.

Developing operations capabilities

Underlying the whole concept of continuous improvement is the idea that small changes, continuously applied, bring big benefits as cumulative total. Small changes are relatively minor adjustments to resources and processes and the way they are used. It happens through the way in which humans learn to use and work with their operations resources and processes. Their understanding, ingenuity and creativity is the basis of capability development.

Learning, therefore, is a fundamental part of operations improvement. Here we examine two views of how operations learn. The first is the concept of the learning curve, a largely descriptive device that attempts to quantify the rate of operational improvement over time. The second is operations’ learning driven by the cyclical relationship between process control and process knowledge.

Process knowledge

Central to developing operations capabilities is the concept of process knowledge.

The more we understand the relationship between how we design and run processes and how they perform, the easier it is to improve them.

For most operations manufacturing persons have at least some idea as to why the processes behave in a particular way. The path of process improvement is along operations managers attempt to learn more. It is useful to identify some of the points along this path.

One approach to this has been put forward by Roger Bohn. He described an eight-stage scale ranging from ‘total ignorance’ to ‘complete knowledge’ of the process.

● Stage 1, Complete ignorance. There is no knowledge of what is significant in processes.

● Stage 2, Awareness. There is an awareness that certain phenomena exist and that they are probably relevant to the process, but there is no formal measurement or understanding of how they affect the process. Managing the process is far more of an art than a science, and control relies on tacit knowledge (that is, unarticulated knowledge within the individuals managing the system).

● Stage 3, Measurement. There is an awareness of significant variables that seem to affect the process with some measurement, but the variables cannot be controlled as such. The best that managers could do would be to alter the process in response to changes in the variables.

● Stage 4, Control of the mean. There is some idea of how to control the significant variables that affect the process. Managers can control the average level of variables in the process, even if they cannot control the variation around the average. Once processes have reached this level of knowledge, managers can start to carry out experiments and quantify the impact of the variables on the process.

● Stage 5, Process capability. The knowledge exists to control both the average and the variation in significant process variables. This enables the way in which processes can be managed and controlled to be written down in some detail.

● Stage 6, Know how. By now the degree of control has enabled managers to know how the variables affect the output of the process. They can begin to fine-tune and optimise the process.

● Stage 7, Know why. The level of knowledge about the processes is now at the ‘scientific’ level with a full model of the process predicting behaviour over a wide range of conditions. At this stage of knowledge, control can be performed automatically, probably by microprocessors. The model of the process allows the automatic control mechanisms to optimise processing across all previously experienced products and conditions.

● Stage 8, Complete knowledge. In practice, this stage is never reached, because it means that the effects of every conceivable variable and condition are known and understood, even when those variables and conditions have not even been considered before. Stage 8 therefore might be best considered as moving towards this hypothetically complete knowledge.

Source: from Bohn, R.E. (1994) ‘Measuring and managing technical knowledge’, MIT Sloan Management Review, Fall 1994, article no. 3615.

The importance of routines of process control

One of the most important sources of process knowledge is the routines of process control. Process control, and especially statistically based process control results in knowledge. Knowledge it is vital to establishing an operations-based strategic advantage.

Ch. 10. Sharpening the Edge: Driving Operations Improvement

in Operations, Strategy, and Technology: Pursuing the Competitive Edge

Robert Hayes, Gary Pisano, David Upton and Steven Wheelwright

2005

https://bcs.wiley.com/he-bcs/Books?action=contents&itemId=0471655791&bcsId=2135

Sections

Introduction

A Framework for Analyzing Organizational Improvement

"Within" vs. "Across" Group Improvement

Learning by Doing vs Learning Before Doing

Transferring Learning from Outside the Organization

Breakthrough vs Incremental Improvement

A Framework for Improvement Activities - with Two Examples

Organizational Implications of Different Approaches

Updated on 17 May 2021, 28 Feb 2021, 4 February 2021

Published on 31 Jan 2021